Notes written for the occasion of Utopia Variations: Gregg Biermann in Person. October 30th, 2014 @ grayDUCK Gallery.

Gregg Biermann. Another Picture (2007)

“The meaning of digital technology lies in its ability to copy, alter, mask, fragment, super-impose, mutate, reflect, transmit and reframe.” Thus says experimental video artist Gregg Biermann, whose work mines the specificity of the digital medium in an attempt to find its horizons of possibility without, however, disintegrating into digital noise. In order to explore these horizons, Biermann often appropriates sounds and images from classic Hollywood films and manipulates digital editing software in order to reconfigure these recognizable scenes into barely recognizable – and yet precisely not unrecognizable – variations and iterations (words which appear in two of his video titles). Indeed, the scenes from Hollywood films, with which most educated film viewers will be familiar, act as a field of shared experience against which our experience of the digital may emerge. Meanwhile, in other works, Biermann manipulates his own footage into kaleidoscopic visual and sonic experiences that similarly mine the depths of the digital medium.

Biermann’s found footage work is reminiscent of some of the films of Austrian filmmaker Martin Arnold including Pièce touchée (1989), Passage à l’acte (1993), and Alone. Life Wastes Andy Hardy (1998), which also reedit Hollywood films. However, whereas Martin’s films – edited using an optical printer – rapidly alternate full cinematic frames for a stuttering effect, Biermann’s work – edited using digital software – intervenes within the frame by dividing or multiplying it in various ways. By using digital algorithms that generate effects that exceed the human ability to fully comprehend them, Biermann’s films produce “inhuman” patterns of which our minds nevertheless attempt to make sense.

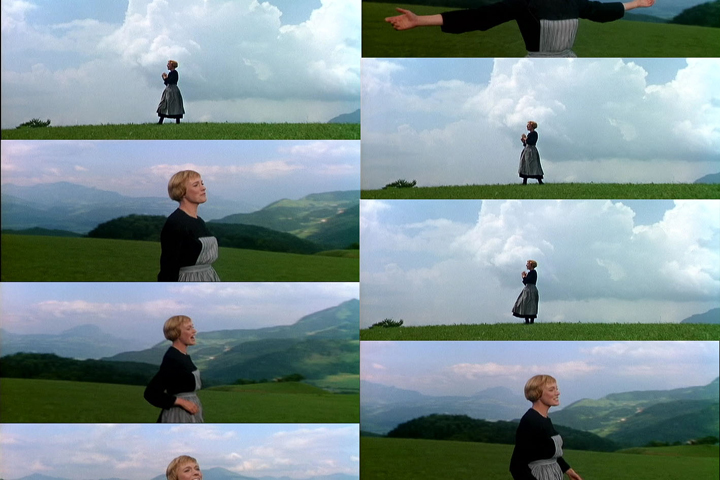

The pleasure of Hollywood musicals often depends on the sense of wholeness and unity produced by each sequence, and by the narrative as whole. Biermann’s work, however, actively undoes this wholeness and unity. In The Hills Are Alive (2005) and Utopia Variations (2008), musical sequences are deconstructed and transformed into an entirely different kind of music, eerie and unsettling. The Hills Are Alive appropriates the iconic opening scene from The Sound of Music (1965), in which Maria sings the title song, and splits the screen into multiple temporally-offset images that alternate, appearing and disappearing, advancing slightly from one to the next, but never resolving into a sense of progression or resolution. In Utopia Variations, the “Over the Rainbow” sequence from The Wizard of Oz (1939) moves forward from the beginning and backwards from the end of the scene in half-second intercuts. One screen splits into two and then four and so on until we are confronted with 25 screens. Dorothy’s single voice is transformed into a “canon” of 25 voices in which each voice is slightly out of sync. Then the process repeats in reverse until the split screen is returned to a single image. In each of these “musical appropriations,” it is as if the computer is trying to analyze the meaning of music, missing the point entirely but simultaneously producing another, fragmented, and fundamentally digital kind of sonic experience – along with its visual corollary.A different but still fundamentally digital experience is generated by Another Picture (2007). Inspired by the chronophotographic work of Étienne-Jules Marey, Another Picture splits the finale from the Hollywood classic Sunset Boulevard (1950) into sixteen superimposed layers within a single image. Each duplicate of the scene dissolves in and out such that it is slightly offset in time from the next. This generates a visual and auditory echo effect and a blurring of the image both across the frame and over the original edits. While superimposition is often used in Hollywood narrative to signify dream, hallucination, or a ghost, this appropriation brings out the hallucinatory, ghostly aspect inherent in every cinematic image, which is always an echo of the “real.” However, it further suggests that digital technology, with its potential to divide the temporality of the image into smaller segments literally ad infinitum, may multiply the intensity of this echo.

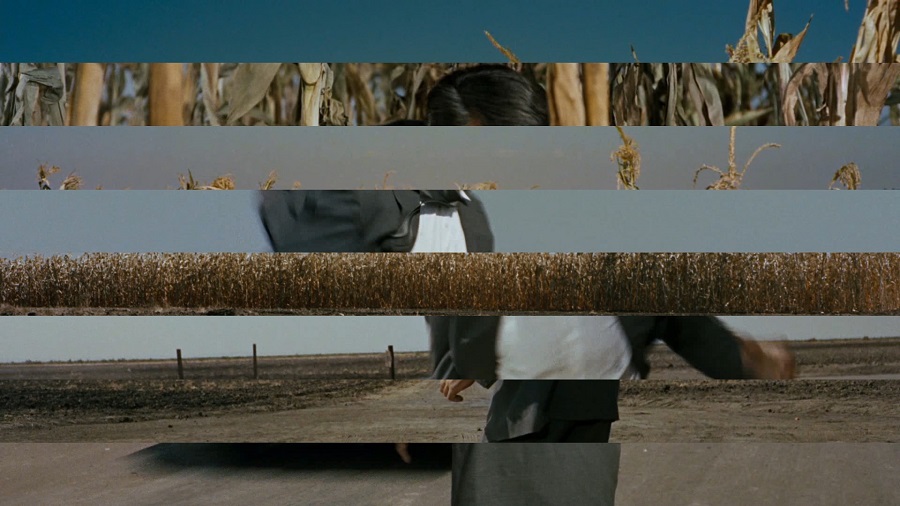

Whereas Another Picture divides the temporality of the image into superimposed layers, two of Biermann’s other films divide temporality into segments along the horizontal and vertical axes of the image, respectively. In Crop Duster Octet (2011), the iconic “crop duster” sequence from Hitchcock’s North by Northwest (1959) in which Cary Grant is repeatedly attacked by a small airplane swooping from the sky is deconstructed into eight horizontal bands, each of which is slightly out of synch with the next. As the scene (and, in particular, Grant’s body) is continuously deconstructed, the patterns of action are refigured and intensified until they reach a crescendo of convergence. Similarly, in Iterations (2014), a sequence from Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) is sliced into nineteen columns, each moving at a slightly different speed, getting progressively faster from left to right. Only at one instant do all nineteen columns briefly align. Like Another Picture, these two films invite us to experience different instants of the scene simultaneously, invoking our desire for time to cohere into a single instant but only briefly allowing for this satisfaction.

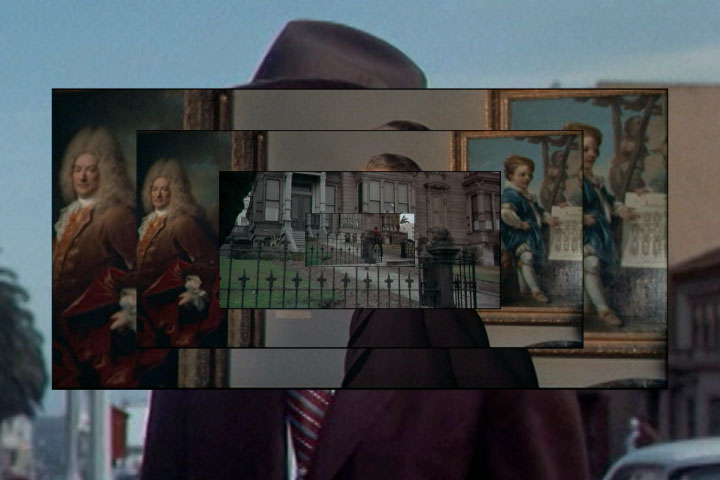

This sense of withholding full coherence and resolution continues in Labyrinthine (2010). In this film, forty-one non-consecutive shots from a single scene in Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) are repeated and transformed into concentric rectangles that grow larger over time, as if emerging toward the viewer. This, of course, generates a similar sense to the “trombone shot” Hitchcock developed for the film – in which the camera pulls away from the subject as the lens zooms in – in order to add a physical sense of vertigo to a point of view shot. However, whereas Hitchcock’s trombone effect maintained the unity of time, space, and vision, Biermann’s reediting creates both a spatial and temporal disturbance that is, moreover, not localized within any one character. Different parts of the same scene – in which Scottie follows and watches “Madeleine” – appear to move ever towards us. Temporally, however, the scene moves forward and backward, so that we are caught in a seemingly endless cycle of following, watching, looking, and following.

Where Labyrinthine produces a sense of endless cycle and regression, Magic Mirror Maze (2012) suggests endless fragmentation. This film takes the famous “hall of mirrors” sequence of Orson Welles’ classic film noir The Lady from Shanghai (1947) and splits it into multiple screens that repeat and flip the image in various ways, disrupting the sound at the same time. Although the original scene is famous for its disorienting effects due to Welles’ ingenious use of multiple mirrors, Biermann’s use of digital algorithms to repeatedly flip and mirror already-fragmented images (and sounds) from this sequence multiply this disorientation exponentially. While the technology of the mirror – or the double mirror – is uncanny in its ability to multiply reality infinitely, digital technology also harbors this potential. A digital “hall of mirrors,” however, suggests a degree of fragmentation – an infinite regression of broken mirrors, perhaps – that goes beyond the ability of the human eye (or ear) to reconstruct as a whole.

The Age of Animals (2014) is a somewhat different beast (pun intended) in that it features not found footage but rather contemporary video footage Biermann himself shot in the Museum of Natural History in Manhattan, the Vatican, and the Bronx Zoo. However, Biermann applies similar manipulations to this footage, producing a complex three-dimensional illusion in which foreground and background are forever trading places. Indeed, the visual experience of this film is akin to being trapped inside an M.C. Escher painting or riding a rollercoaster after taking a hallucinogen. Yet we can still see the documentary world though these disorienting distortions. In the Museum of Natural History, we see visitors looking at taxidermic animals lost to extinction along with the skeletons and footprints of dinosaurs and other bygone species. A sign reading “What makes the Earth habitable?” spins by, implying the fact that the Earth could very well become uninhabitable. In the Vatican, we see tourists videotaping and photographing the soaring ceilings dedicated to the Creator of animals according to Christian theology. The opposition between the spaces of the natural history museum and the church is emphasized through the soundtrack. This alternates between a repeated segment of sampled choral music, silence, and a recorded interview with paleontologist Peter Ward who laments the politics surrounding the discourse on global warming and evolution as well as the misguided notion that previous mass extinctions were caused only by asteroids and not by changing temperatures. The space of the Bronx Zoo, framed by the soundtrack and the other two spaces, reads not as a space of joyful childhood discovery, but rather as the last living relics of the coming mass extinction caused by human ingenuity and greed. Despite the visual distortions, we recognize tortoises, gorillas, giraffes, birds, and so on, but they, too, are barely recognizable in that they suddenly read as the last of their kind. Whether these animals are the product of supreme Creator or evolution becomes irrelevant if they are doomed to disappear. The very title of the film “Age of Animals” implies that the age can end, that there may soon be an age without animals. This film suggests that in the political opposition between science and religion, the casualties are entire species – perhaps all of them.

As a whole, Gregg Biermann’s recent work suggests a sense of the overwhelming in a historical moment in which we are disoriented visually, sonically, socially, politically, and even biologically. It reflects and refracts the sense that, even as we attempt to make sense of the contemporary world, it continues to shift, becoming a foreign and unfamiliar territory. In Biermann’s work, as in contemporary life, our landmarks are constantly shifting, forcing us to find new ways of locating ourselves in a spatial and temporal situation that is ever slipping beyond our mind’s grasp.♦

Jaimie Baron is an Assistant Professor of Film Studies at the University of Alberta. Her research interests include media theory, experimental film and video, documentary film and video, appropriation, and digital media. Her first book, The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History, was published by Routledge Press in January 2014. She is also the founder, director, and co-curator of the Festival of (In)appropriation, a yearly international festival of short experimental found footage films.