Notes written for the occasion of PLATONIC: Dani Leventhal in Person. January 31st, 2015 @ MASS Gallery.

With their intuitively apt and propulsive editing, Dani Leventhal’s videos are often discussed in terms of their montage. When I wrote about Leventhal’s work for Cinema Scope (“The Multitude of Visible Things,” Issue 47, Summer 2011), I discussed her approach to editing in relationship to her background in sculpture, “creating form out of an accumulation of material.” (A broken hand while working on her MFA in sculpture at the University of Illinois at Chicago led her to temporarily turn to video. The medium proved so aligned with her interests that she went on to get a second MFA, in film/video, from Bard College.)

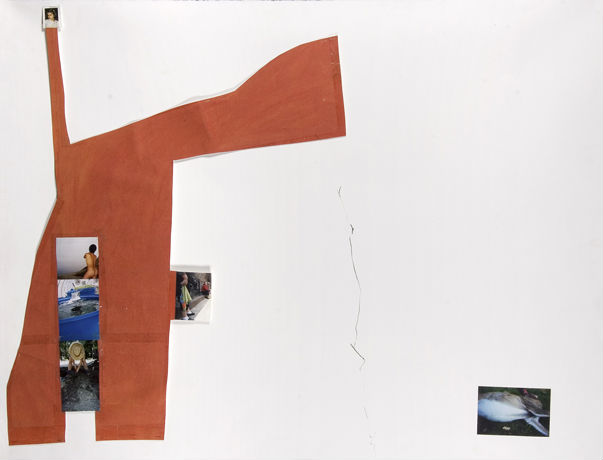

Since writing that article, another aspect of Leventhal’s artistic practice has grown in prominence in her videos. Parallel to her videos, she has an equally distinctive and dedicated commitment to drawing; she is currently an Assistant Professor in Drawing at The Ohio State University and her drawings are in the permanent collections of MoMA, Yale, and many other institutions. Aspects of her drawings are intertwining with her videos in increasingly deepened ways. While maintaining their devotedness to capturing unblinkered, representational images of the world, the videos have developed a more pronounced interest in abstraction. The video Tin Pressed presents a quintessentially Dani Leventhal scene in which the filmmaker records her own mammogram, but the framing cuts off her head so that her body becomes a nearly personless shape interacting with the shape of the medical equipment:

The scene ties into the video’s larger themes of constraints – fighting against and giving into – but it also recalls the abstractions that Leventhal is predisposed towards in her drawings, which are often dominated with shapes that are taken from nature and abstracted, or grow out of photographs imbedded in the drawings themselves. Compare the primary shape in this earlier drawing with the composition of the above screengrab:

This shift towards abstraction may be indicative of a larger shift in Leventhal’s work. Rather than providing an introduction or explication of her work, these program notes will serve as speculations about the directions her work is taken. A shift that’s well represented by the four videos in the program at Experimental Response Cinema.

Draft 9 (2003) represents as auspicious a debut film as the experimental film community has seen. Featuring a fully formed voice, the video is full of fearlessness, tension, ruthless empathy, and overwhelming intimacy. It’s hard for me to resist the temptation to use these notes as an occasion to provide a shot for shot running commentary track for this video. I’m not the only person to think this among the most momentous, indelible works of my generation. No subsequent videos from Leventhal emerged for a few years until she began the program at Bard. The years 2007-08 saw a flurry of pent-up videos. Often dealing with overseas travels (Israel in Show & Tell in the Land of Milk and Honey and Skim Milk & Soft Wax; Lithuania in 9 Minutes of Kaunaus; among several other destinations and videos), these videos are almost reckless in their abandon. Liberated by the exhilarating freedoms of Draft 9, Leventhal applied a less rigorous and almost too provocative approach towards all aspects of her personal, political and social lives in this string of videos.

2009 saw an artistic renewal in her videos with 54 Days this Winter 36 Days this Spring for 18 Minutes. As the title implies, it’s a video all about structure and restriction. Forcing herself to shoot for 9 minutes a day, every day, for the number of days contained within the title, the video provides the productive occasion for Leventhal to indulge in the discipline of artmaking. The tempering of recklessness. The virtues of limitations.

This tendency finds its most precise realization within her next videos: Hearts Are Trump Again (2010) and Tin Pressed. At half the length of 54 Days, Hearts Are Trump Again provides a more potent précis of Leventhal’s project. It introduces fictional elements that she increasingly explores in subsequent works. As a film curator at the Wexner Center for the Arts, I had the luxury of seeing a very early cut of Tin Pressed as it was being edited in our Film/Video Studio Program. That rough cut was considerably longer than the final cut that was released to the world. I’m still uncertain as to which version was superior. There are elements of the longer cut that I still fondly recall. The final release version comes in under a very succinct, dense seven minutes. Condensing has clearly become important to her work. The final version is a jagged little shard. And probably all the more potent for it. Filmed primarily, but not exclusively, in Israel, Tin Pressed makes much less of an attempt to make an articulated statement about the current state of Israel and/or Palestine than her earlier videos on the subject. Instead it shows the artist’s honest reluctance to make such pronouncements. It approaches issues glancingly, and perhaps more resonantly, than a direct address would. The shots that bookend the video illustrate this quite well. The final shot sees Leventhal reveling in the beauty and pain of an Israeli drag performance—a personification of dualities in the same body. But the opening shot is what I’d like to focus on. In the shot, the filmmaker is lying on a hard asphalt surface as towering (male?) figures kick her fetal figure with abandon. In the in-progress version of Tin Pressed I remember this shot lasting for several minutes. There were interactions between the kickee and the kickers. Perhaps safe words were uttered? In any event, it was clear that there was consent between the artist and her assailants. A tension between fiction and reality was established. Games or brutality? Is there a fucking difference? In the final version, that scene lasts less than 30 seconds and it comes across as straight documentary footage without any interplay between the woman on the ground and the assailants towering above her. It’s perhaps even more troubling this way. The scene is over before we can understand it. Rather than fully exploring the interplay between the woman being kicked and her assailants, the scene introduces an air of uncertainty and violence and tension that lingers over the rest of the video.

Platonic (2013), produced a few years after Tin Pressed, follows up on this tone. An examination of desire and its dangers, the video is the most thorough exploration of many of her themes. Whether it is a dead end or an opening to new destinations remains to be seen. The fearlessness of Draft 9 is long gone. Dani is now asking for permission from her subjects before filming. She’s no longer filming the unfilmable, instead she’s filming the permissible. It’s unquestionably a more ethical approach. But do ethics make for the best art? In Draft 9, Leventhal tries to bridge the gap between herself and the other (in its many forms), but a decade later by the time of Platonic, she is much more attuned to those concerns and has internalized them. This, of course, allows her to explore new directions. Platonic, in particular, features striking scenes of re-photography where Leventhal projects video onto a corner or wall and films that projection. Indicative of the new self-awareness that has entered her work, these scenes add a new element of mediation into her image-making. The photographed image becomes its own subject. A space that can be analyzed and re-interpreted. A space of memory rather than present tense. After the raw authenticity of Draft 9, calling Platonic self-aware can seem like a pejorative. But the more self-conscious register of Platonic can explore more nuanced aspects of the human experience, like memory or materiality, rather than the raw, barely unmediated experience of existence as presented in Draft 9. We, as viewers, are fortunate to be able to witness an artist modulate between youthful and mature registers of art making, all within a single decade. Each new dead end that the artist encounters is only a new opportunity for trespassing.♦

Chris Stults is the Associate Curator of Film / Video at the Wexner Center for the Arts (Columbus, Ohio).