Film notes by Jennifer Stob

The film

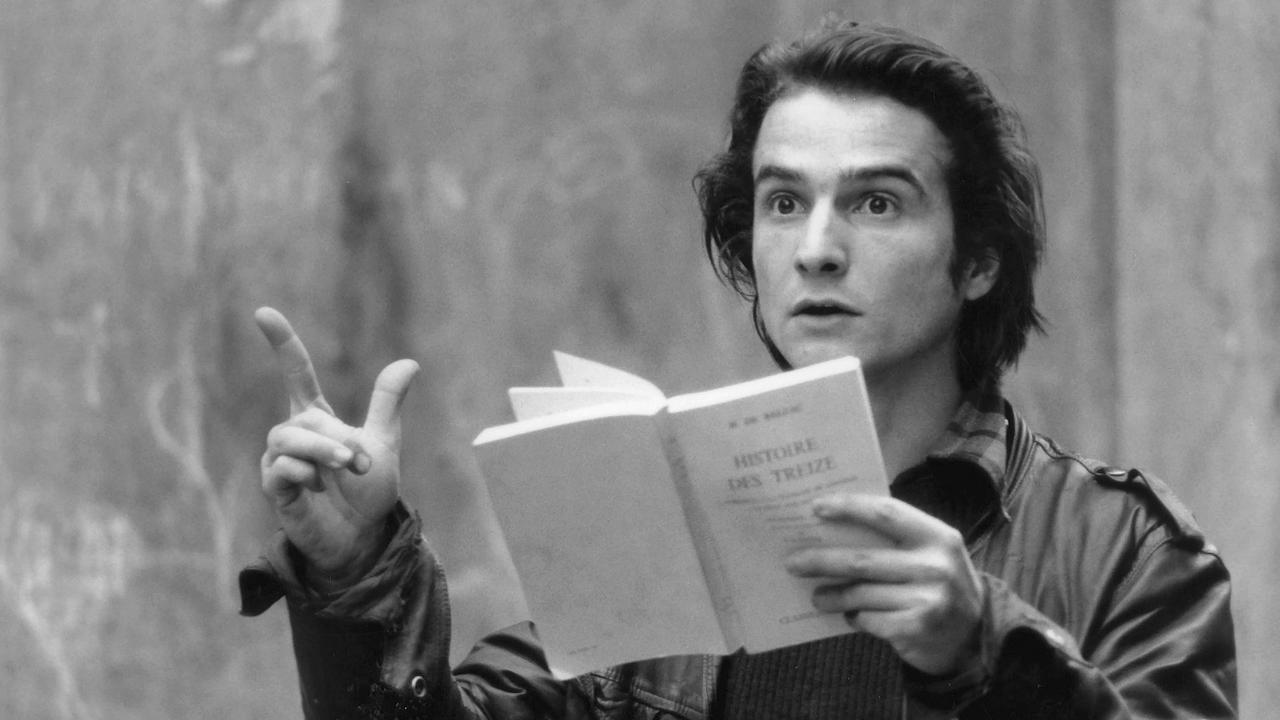

The footage for Out 1 was shot over six weeks in April and May of 1970. It was shot on 16mm with large film magazines. This format allowed Rivette to save money and allowed his cinematographer, Pierre-William Glenn maximal mobility, speed and flexibility in composing shots. There was no script—only a thirty- to forty-page chronology that director Jacques Rivette assembled with assistant director Suzanne Schiffman roughly a week before shooting began. The cast did not have access to this chronology; Out 1 was the first of Rivette’s films that was completely improvised. The participation of dynamic young actors and actresses from Paris’s film and theatre community like Jean-Pierre Léaud, Juliet Berto, Michael Lonsdale and Bulle Ogier was a staggering leap of faith and an enormous investment of time, energy and cooperative focus. Numerous film critics (among them, Michel Delahaye, Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, and Eric Rohmer) as well as producer Stéphane Tchalgadjieff also appeared in the film. Rivette edited his material with Nicole Lubtchansky over the next sixteen months into a twelve-hour, forty-minute cut that he titled, Out 1: Noli Me Tangere.

The astonishing length of the film was the result of Rivette’s passionate desire to document the ludic quality of human thought unfolding over time: during rehearsals, meandering conversations, lonely ruminations, arguments and community-building. Rivette was an admirer of the ritualized and process-based “nonfictional acting” of the Living Theatre, an American theater company founded by Julian Beck and Judith Malina in 1947. For Rivette, bodily gesture and facial expressions communicate thought as much as words ever could, and the exploration of the call and responses formed by this non-verbal communication are responsible for many of the film’s long takes.

As a result of its length, a plan was developed to show Out 1 as a television serial. French television refused it. On October 9 and 10, 1971, a work print of the film was shown in Le Havre, France. This was the only theatrical screening of the film in its complete length until 1989. German television agreed to broadcast a four-hour, fifteen-minute version that Rivette and Denise de Casabianca had spent an additional twelve months editing. That version, entitled Out 1 Spectre was shown in two parts in Germany on December 25, 26, 27 and 28, 1972. Out 1 Spectre was shown on June 30, 1973 at the International Forum of Young Film in Berlin, Germany and on March 28, 1974 in France. In 1989, Out 1 was shown in its full length at the Rotterdam International Film Festival, but with an incomplete soundtrack. Thanks to West German Broadcasting’s purchase of the film for television, Rivette was able to reconstruct the missing soundtrack in 1990.

Asked about the enigmatic subtitle of the original Out 1 in 1990, Rivette explained,

Noli me tangere (touch me not) is a well-known motif in Renaissance painting and in religious painting in general…after the Resurrection, Christ encounters Mary Magdalene, who nears him, but he says to her, Noli me tangere, touch me not. He departs, without saying anything further…I first thought of calling the film that during the editing. Out 1 is a film in which people move toward each other without really being able to touch each other. As soon as they get close, something like a countercurrent (as with electricity) occurs that separates them immediately. There are many moments of “approachingoneanother” in the film that are nevertheless always—almost always—interrupted: noli me tangere – touch me not.

And the title itself? Meaningless, Rivette had declared in 1974:

The title, Out 1 is a false title, a mere label that is meant to be written but not spoken aloud. It’s a purely written title that I hope has no meaning. It is “OUT,” and after that, the number “1.” It is a temporary title, but there will be no definitive title—or if so, only one for the four-hour and fifteen minute version [called SPECTRE] and only for commercial reasons.

The director

Rivette was one of the most fresh and important voices of French cinema in the 1950s and 1960s, writing and briefly serving as editor-in-chief for the era-defining journal, Cahiers du Cinéma. He began his foray into filmmaking in 1958 with Paris Belongs To Us, released in 1960. The film contains many of the leitmotifs of spontaneity, conspiracy, societal simulacra and subversive conviviality that Rivette would continue to explore over his oeuvre. His film, The Nun was the victim of government censorship in 1966 and became a cause celebre for cinephiles internationally. Rivette took part in short-lived, collaborative projects in filmmaking as well as in everyday life during France’s social uprisings of 1968. This experimentation, its lessons and its failures infuse his films of the subsequent decade. Céline and Julie Go Boating (1974), one of his most lighthearted, commercially successful and critically acclaimed films, is a testament to Rivette’s unique ability to command unconventional, show-stopping performances from the theatrical ensembles he casts. Rivette won the Grand Prize of the Jury and the Palme d’Or at the 1991 Cannes Film Festival for La Belle Noiseuse (1991). His latest and last film, 2007’s The Duchess of Langeais (Ne touchez pas la hache) was an adaptation of the second novel in Balzac’s History of the Thirteen, which also inspired Out 1.

The inspiration

Rivette was fascinated with the convergence and dissolution of collectivity, and the theme pervades all of his films. Out 1 is inspired by and explicitly references Honoré de Balzac’s trilogy, History of the Thirteen (1833-1835). Here, an excerpt from the novel’s preface that gives a sketch of the utopian, revolutionary collectivity featured therein:

There were brought together under the Empire and in Paris, thirteen men all equally possessed by the same sentiment, all of them endowed with sufficient force to remain constant to one idea, sufficiently honorable not to betray one another, even when their individual interests conflicted, sufficiently politic to conceal the sacred ties which united them, sufficiently strong to maintain themselves above all law, courageous enough to undertake anything, and fortunate enough to have almost always succeeded in their designs; having encountered the greatest dangers, but never speaking of their defeats; inaccessible to fear, and having trembled neither before the prince, the headsman, nor innocence; accepting each other for such as they were, without taking into account social prejudices; criminals undoubtedly, but certainly remarkable for some of those qualities which mark great men, and recruiting their number only from men of distinction.

[…]Thus equipped, immense in action and in intensity, their occult power, against which the social order would be defenseless, might overthrow in it all obstacles, overwhelm all wills, and give to each one of them the diabolical power of all. This world isolated in the midst of the world, hostile to the world, admitting none of the ideas of the world, recognizing none of its laws, submitting only to the conscience of its own necessity, obedient to devotion only, acting altogether for one of the associates when one of them claimed the assistance of all; this life of buccaneers in kid gloves and in carriages; this intimate union of superiors, cold and mocking, smiling and cursing in the midst of a false and mean society, the certainty of being able to make everything bend under a caprice, of contriving a vengeance skillfully, of living in thirteen hearts; then the continual satisfaction of having a secret of hatred in the face of men, of being always armed against them, and of being able to retire into one’s self with one idea more than even the most remarkable men could have; — this religion of pleasure and of egoism fanaticized thirteen men, who reconstituted the Society of Jesus for the profit of the Devil. It was horrible and sublime. And in fact the compact was made; and in fact endured, precisely because it appeared impossible.

There were then, in Paris, thirteen brothers, who belonged to each other and who did not recognize each other in the world; but who came together in the evening, like conspirators, hiding none of their thoughts from each other, using alternately a power like that of the Old Man of the Mountain; having a foothold in all the salons, their hands in all the strong-boxes, elbow-room in all the streets, their heads on any pillow, and, without scruple, making everything serve their fantastic will. No chief commanded them, no one could arrogate to himself the supreme power; only, the most vivid passion, the most exacting circumstances, assumed the initiative. They were thirteen unknown kings, but really kings, and more than kings, judges and executioners who, having made for themselves wings with which to traverse society from the top to the bottom, disdained to be something in it because they could be all.

La revolution manquée

It’s difficult to overemphasize the shadow that the year 1968 casts on Out 1. It was a year of international revolutionary ferment that, in France especially, seemed to vanish in thin air with no meaningful political changes effected. Longer lasting, however, was the desire to question social conventions and experiment with ways to subvert the postwar consumer culture that seemed to so thoroughly infuse human relationships. The paranoia, the manipulation, the parody, and the quixotic hopefulness in Out 1’s protagonists are a sympathetic but unsentimental portrait of a counterculture losing traction, unsure what (and if) the next project should be. Subsequent generations will notice that, by assembling an intrepid group of outsider cinephiles with enough stamina to engage with the story it tells, Out 1 suggests that something like this counterculture and its many alternative socialities might yet be reconstituted.

OUT 1 – NOLI ME TANGERE

From Lili to Thomas

We are introduced to two theater troupes, one lead by Lili, the other by Thomas. Colin is a mute (it seems) who plays his harmonica and sells book pages as fortunes in cafés. Frédérique strikes up conversation with strangers, angling for money.

From Thomas to Frédérique

Colin receives several mysterious messages. He attempts to decode them. Frédérique continues her hustle. Lili meets with Lucie, who tells her that Igor has disappeared. We learn Lili was once part of Thomas’s theater troupe.

From Frédérique to Sarah

Colin visits a Balzac expert in an attempt to understand the puzzling messages he has received. An attempt to decode one leads him to the shop, “The Angle of Chance.” He meets Pauline and her friends. Thomas and Béatrice continue their theater exercises. With the feeling that not enough progress is being made, Thomas decides to leave Paris and seek refuge with Sarah, who lives in a large seaside mansion.

From Sarah to Colin

Colin tries to get a press pass in order to disguise himself as a journalist and penetrate the circle of individuals he met at “The Angle of Chance.” Pauline remains mysterious. Frédérique charms her way into the house of Étienne, searches through his things, takes a packet of letters, and finds more clues about “the thirteen.” Thomas visits Pauline (who also goes by Emilie). We learn Igor is her husband. Has he vanished purposely or by accident? Renaud joins Lili’s theater troupe.

From Colin to Pauline

Frédérique dresses as a boy and tries to blackmail Lucie, using the letters she found at Étienne’s house. Colin falls in love with Pauline. Thomas is torn between Sarah and Béatrice. Lili stands helplessly by as her troupe seems to dissolve around her. Frédérique tries her luck with Pauline, who hopes to find news of Igor in the letters that Frédérique has stolen.

From Pauline to Emilie

Colin meets Sarah in Pauline’s shop. He follows her to Thomas’s project space. He questions Thomas about “the thirteen,” but gets no satisfactory answers. We learn that Pierre, Étienne, Lucie, Thomas, Lili, Sarah, Igor and Warok used to be members of this “groupe of thirteen,” that now seems to have broken apart. Frustrated with Renaud and her theater troupe, Lili escapes to the seaside mansion. Thomas tries to start a ménage à trois. Colin is thrown out of Pauline’s shop. Frédérique strikes up a conversation with Renaud and promises him secrets.

From Emilie to Lucie

Renaud and Frédérique meet in the Parc Montsouris. Colin meets Warok, and his suspicions of conspiracy grow. Emilie/Pauline decides to destroy Pierre’s career but Sarah feels compelled to prevent this from happening, and tries to reunify Thomas, Étienne and Lucie.

From Lucie to Marie

Frédérique meets a tragic end. Colin decides that the story of the “thirteen” was ultimately only child’s play. After the group’s awkward rendez-vous, Thomas is stranded on the seaside, tragicomically alone.

Rivette citations and chapter summaries are based in part upon film notes prepared for the 41st International Filmfestival, Berlin Germany, 1991.