Harun Farocki wrote the following curatorial text on Michael Klier’s Der Riese in January 2014 for the #VIDEOTAPES series at the neuer berliner kunstverein ( n.b.k.) in Berlin, Germany. ERC screened Der Riese on April 29th, 2015 at the Alamo Drafthouse Ritz. Text translated by Fjoder Donderer. Edited by Ekrem Serdar and Jennifer Stob.

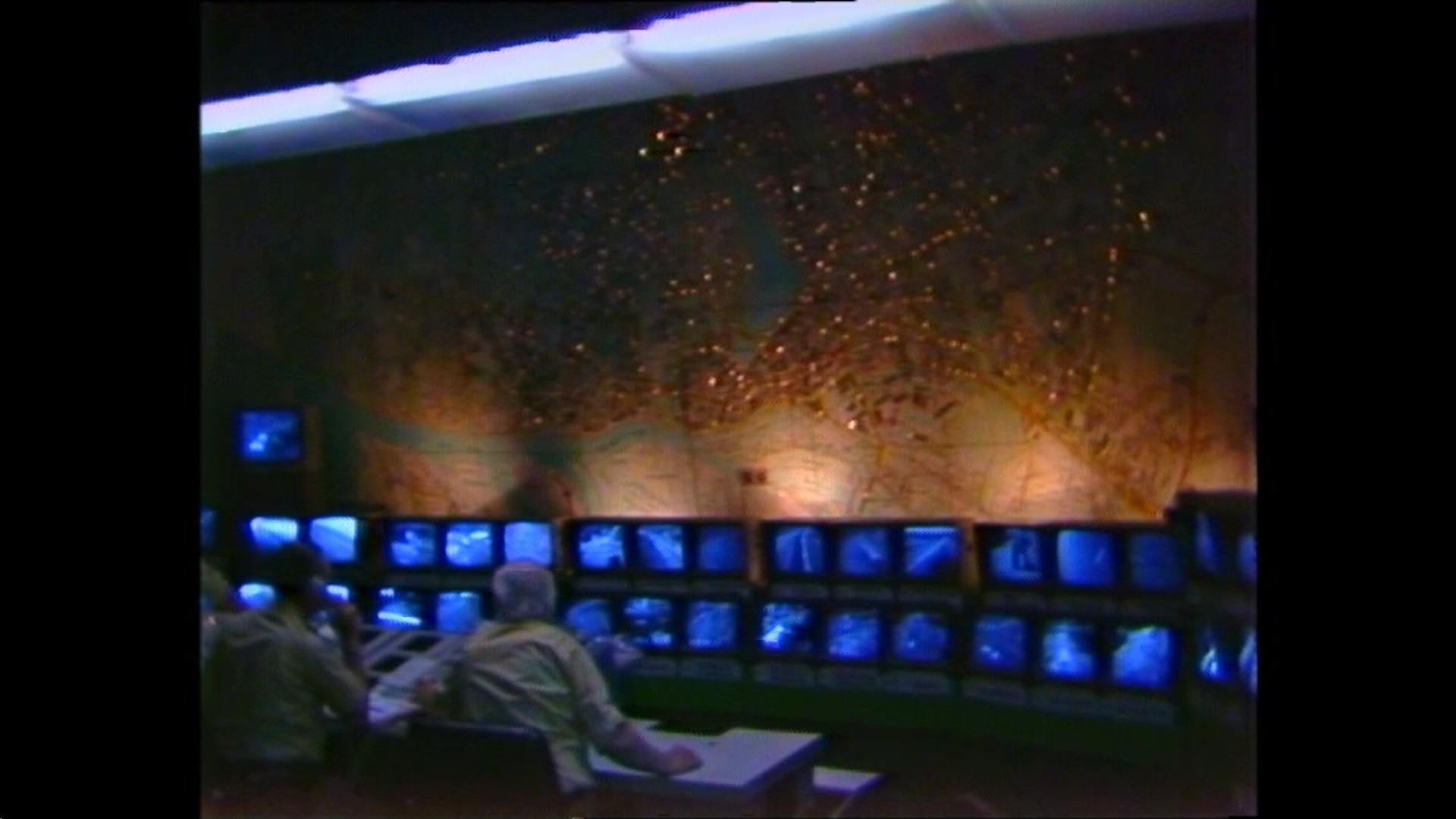

Michael Klier’s film is composed of images taken from surveillance cameras. In 1983, video surveillance was still a novelty. When in those days one was filming in the street, even if just with a video camera, passers-by would stop and ask when it was going to be broadcast. One assumed the person handling a camera was of a certain importance. Today, digital cameras are integrated in all sorts of devices, such as the locomotives of model railways, and in almost every mobile phone. A camera today has no greater value than a ball-point pen.

And soon one will probably find it insulting to be given a camera as a gift. Being filmed is also something most people have become accustomed to. They do not disturb the film shoot by waving or by looking into the camera. They know that they are constantly, in a way, indirect persons of contemporary history, and have thus forfeited the right to their own image.

In 1992, during the war of the Allies against Iraq, the press office of the U.S. military released special surveillance images: images from cameras that were installed at the nose of projectiles approaching their targets. Filming bombs with disposable cameras. It was said that these projectiles were intelligent weapons and so the two terms “surveillance images” and “intelligent” suddenly attained some proximity.

When in 1983, for instance, there was a monitor in a subway station with the image of the platform, many looked at it. What was there to see? An image, perhaps not attractive, but at least out of the ordinary: an image that was not intended to entertain or educate. That didn’t actually want to be an image. The camera helped the driver survey the platform, as a mirror would have done. The channel function of the medium. Technical images, operational images.

The French philosopher Roland Barthes postulated an operational language, as opposed to the common mythological one ¹. The lumberjack who fells the tree, speaks the tree and not about the tree. Hard to imagine that an image can be nothing but a tool – but their ambition to be nothing but a tool has quickly generated attention for surveillance images.

In the film M (1931) the police set up a dragnet in search of a child murderer. There is a letter claiming responsibility, written on a warped surface. Police officers make house calls to all convicts of sexual assault of children and check if any tabletops there have warped surfaces.

In Hamburg in the early 1980s, during the dragnet for terrorists, the police first investigated who did not pay their electricity and gas bills by direct debit, but in cash at post offices. These were just a few hundred people. Then anyone over 60 was ruled out. In this way, the apartments of the terrorists were located.

This method is hardly heroic. It counters the desire to murder a child or the terrorist act with a dispassionate, structural investigation.

Guided weapons today are controlled from desks, at fixed working hours, and without the perpetrators having to leave their families. War is no longer a state of emergency.

For crime or police films today it must be increasingly hard to describe the fight against crime as anything other than a bureaucratic act.

We pay for the images we watch on television—although not much, hardly more than for heating—however, we have to pay people to watch surveillance images. They do not get much. Experts have been working on image processing, on sensors that automatically recognize anything dangerous or illegal for a long time now.

Before cameras were so cheap that you could get them for next to nothing, Klier abstained from his own image-making and drove around for months with a recording device, recording surveillance images and also copying archival ones.

He called his film The Giant. A giant is strong but not particularly intelligent. One can well imagine the giant, when watching images taken by cameras from a great height. The invisible giant clumsily pans the camera and pulls the zoom. He tries to frame a sailboat, a pair of lovers. He takes pictures of what is “beautiful,” what he therefore wants, or he wants to beautify what he wants to have.

With his montage and its musical accompaniment, Klier puts images in the subjunctive form: could these be the images of a film narrative? A productive misconstruction.♦

¹ See Barthes, Roland. “Myth as Stolen Language.” Mythologies. Trans. Annette Lavers. New York: Hill and Wang, 1972. (ed.)

Harun Farocki (1944-2014) was born in German-annexed Czechoslovakia. From 1966 to 1968 he attended the Deutsche Film- und Fernsehakademie Berlin (DFFB). In addition to teaching posts in Berlin, Düsseldorf, Hamburg, Manila, Munich and Stuttgart, he was a visiting professor at the University of California, Berkeley.

Farocki made close to 120 films, including feature films, essay films and documentaries. He worked in collaboration with other filmmakers as a scriptwriter, actor and producer. In 1976 he staged Heiner Müller’s plays The Battle and Tractor together with Hanns Zischler in Basel, Switzerland.

He wrote for numerous publications, and from 1974 to 1984 he was editor and author of the magazine Filmkritik (München). His work has shown in many national and international exhibitions and installations in galleries and museums. (via Video Data Bank)