Nothing short of revolution can restore to man that divine spirit which he has been denied in our society. As a film-maker and a human being I am devoted to this ideal. As a film-maker I believe that the only hope for motion pictures is the experimental film…It is the responsibility of the avant-garde to remain eternally revolutionary… Cinema remains the youngest of the arts and contains the elements of eternity: meaning poetry…Visions which shall belong to that unknown species that will inherit the real Earth.

~Gregory J. Markopoulos

As a film student at the University of Southern California in the 1940s, Gregory J. Markopoulos, like his close friend and collaborator Kenneth Anger, observed the Hollywood machine at first hand. Witnessing the creative process on the sets of directors such as Alfred Hitchcock and Fritz Lang, Markopoulos also attended a course on directing by the great Josef von Sternberg at USC, and he would come to incorporate the modernistic, European stylings of such maverick Tinseltown directors into his own experimental mode of filmmaking. Beginning as an assistant to both Anger and the third wheel of their unholy trinity, the avant-garde/exploitation filmmaker Curtis Harrington, Markopoulos made a number of films in the United States and Europe before settling permanently in Greece, his ancestral and spiritual home, in the late 1960s. His film works include the trilogy Du Sang, de la Volupte et de la Mort (1947-48); The Dead Ones (1949); Swain (1950); Flowers of Asphalt ( 1951); Serenity (1961); Twice a Man (1963); The Death of Hemingway (1965); Galaxie (1966) and Gamellion (1968). Screenings of such works are rare to say the least and, with one or two exceptions, none of the films have ever been transferred to DVD.

An actor, poet, painter and film theorist (publishing articles in Film Comment, Film Culture, and The Village Voice, among others), as well as the writer, director, and editor of his own films, Markopoulos’ cinema embodied the midcentury American avant-garde’s romantic preoccupations with both classical myth and (homo)sexual identity, and he is widely regarded as among the most accomplished and poetic of the second wave of American experimental filmmakers that orbited around Jonas Mekas in New York City throughout the 1960s. In 1967, Mekas in fact proclaimed Markopoulos, Stan Brakhage, and Andy Warhol to be “our three most talented film artists (and) also our most productive.”

A meticulous craftsman who saw his own art as in lineage to the works of classical Greece, Markopoulos has often been overlooked due to the attention bestowed on the more scandalous and less artistic, technically-inclined, and idealistic representatives of 1960s underground cinema. In the queerly-tinged camp underground of the era, he was a man apart in his embrace and pursuit of high ideals and “high art.” In 1974, he notoriously broke with the Mekas-run grassroots distributor/exhibitor Anthology Film Archives and later that same year, demanded that the meticulous chapter on his work be withdrawn from Visionary Film, P. Adams Sitney’s seminal if not definitive study of the American avant-garde at the time. Self-exiled in Athena, Markopoulos continued the quest to fulfill his intensely personal and independent vision alongside his partner Robert Beavers until his death in 1992.

The Illiac Passion is a tenuous retelling of Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound as famously translated by Henry David Thoreau, and also borrows from Shelley’s reinterpretation of the same myth, Prometheus Unbound. The film takes its title from the iliac region of the human body, the locus of the liver that houses Prometheus’ passion and provides the site of his torture by Zeus. As was typical for Markopoulos’ ambitious film projects, The Illiac Passion’s journey from script to screen was long and arduous. Part of the Markopoulos filmmaking process involved his attempt to seek out and study every bit of information ever written upon his chosen subject. These efforts would then be followed by an extended period of reflection and note taking that could last years before deciding the shape the project might ultimately take. This process definitely contributed to the illusory and fragmentary nature of his major works, where his primary literary and historic sources are often buried deep beneath layers of meta-narrative and obscure, tangential references. He had first drafted a Prometheus screenplay in California the 1940s, finally cast and shot the film in New York throughout 1963 and 1964, and did not commence editing until the following year. The project was then shelved due to lack of funding for striking a final print and was not publicly screened until 1967.

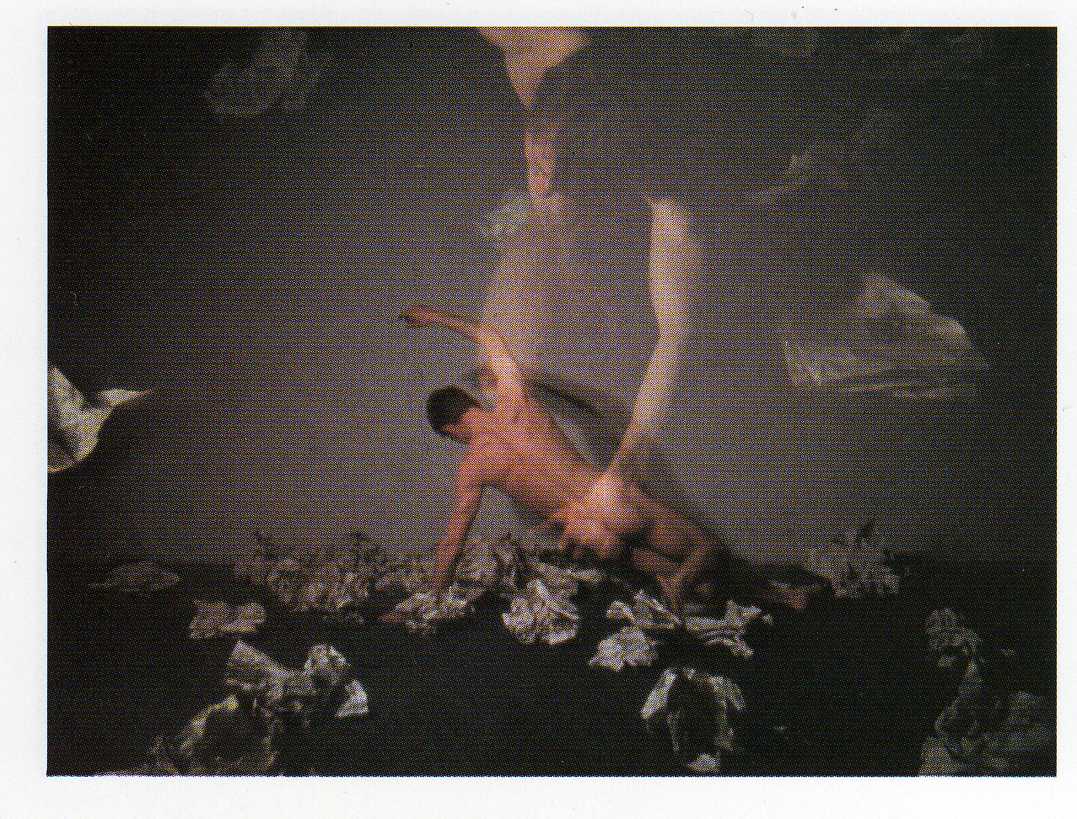

While The Illiac Passion is one of the benchmarks of Markopoulos’ work, it both typifies his oeuvre and is a departure from it. The film’s mythic themes and iconography, the vibrant colors, superimpositions and multilayered images; its progressive editing and sound techniques, all are standard for Markopoulos, as are the surreal dreamscapes conjured from the work’s varied locations, the beautiful (often nude) actors featured throughout, and the film’s pervasive sense of timeless exotica. A fervent audio experimenter, the soundtrack consists of Markopoulos’ own fragmented voiceover narration of the Thoreau text (including some improvisations) and two selections of classical music, creating a complex soundscape appropriate to the filmmaker’s mingling of myth with modernism. Gary Morris, writing of the film for Bright Lights Film Journal in 1997, stated that “The imagery in The Illiac Passion is striking in its hypnotic repetitions;” its characters “unable to move, perhaps trapped in the director’s powerful mise-en-scene…[Markopoulos] reads from Thoreau’s translation of Prometheus Bound but ‘edits’ the words just as he does the images, repeating phrases as if they were chants, with the repetitions alternating with silences.” While we can no longer call upon the author of this Passion to explain, Markopoulos, a brilliant polemicist of his own work, talked and wrote about the film a great deal during his lifetime, allowing interested contemporary viewers to unpack the film’s trancelike images and symbolism and to situate it as a chapter within Markopoulos’ larger body of work with his consistent themes and style.

The choice of the film’s casting, however, is somewhat unusual for the director, comprised of a sort of who’s who of the New York underground art and film scenes circa 1964, and in contrast to his usual practice of casting largely unknown (non)actors. Markopoulos was an extremely cultured, high-minded artist steeped in Classical studies, and was somewhat dismissive of the camp-trash aesthetic that had by the early sixties in New York overtaken the romantic queer cinematic expression inaugurated by the Anger-Harrington-Markopoulos contingent in 1940s Los Angeles. But for The Illiac Passion he believed that the strong and unique personalities of such a rich if dissipated social scene would serve to mirror the archetypal stature of his fallen Greek Gods. Here we have Andy Warhol as a pop art Poseidon, Paul Swan as an aged Zeus, Jack Smith as a zany, ambiguous Orpheus, Beat film comedian Taylor Mead as a Chaplinesque demon sprite, and Gerard Malanga as the hip, gorgeous Ganymede. Film Culture art critic Gregory Battcock, blues singer Tallie Brown, and the popular vampiric underground film and theater diva Beverley Grant also make appearances in the film.

Like his friend Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1966), the film appropriates a pantheon of forgotten deities for a new generation of myth-seekers, in this case contemporary homosexual artists adrift in the modern urban experience. Markopoulos saw in the acute alienation of urban modernity an abhorrent reverse mirror of the classical Greek celebration of beauty, sexual desire and aesthetic fulfillment. But interrogating sexual identity in an increasingly cynical and far from romantic American nightmare was only part of his project. Commenting on the film in 1968, he described a complex artistic dilemma that was typical of the cultural era- The reconciliation of the classical narrative form with that of the experimental, the beauty of the romantic tradition with the starkness of the neobeat era, the forging of an original and personal cinematic language that maintained ties with the romantic tradition. This tension between modernity/modernism and the Classical/ mythological was an ongoing preoccupation for Markopoulos; and his body of work- whether film, or painting, polemics or poetry- engaged this very dilemma. The various facets of his creative expression were but strands of a single thematic project: High art as a very ancient, very necessary vessel for transcendence, rising like a phoenix from the ashes of Twentieth Century civilization.

Philip R. Fagan

ERC

Special Thanks to the Temenos Foundation and Robert Beavers for providing the 16mm print for this extremely rare screening.