Notes written for the occasion of FILMS FOR ONE TO EIGHT PROJECTORS: Roger Beebe in Person. January, 25th, 2015 @ Alamo Drafthouse at the Ritz.

Film Notes¹

Roger Beebe is ubiquitous in the experimental filmmaking world—as a filmmaker he has presented a hundred-and-fifty or so solo screenings, and he regularly tours with up to eight projectors. He produces an unusual variety of new work, and though he is academically engaged with film culture, theory, and philosophy, nevertheless in making films he uses his gut as much as his head, and he takes chances. Beebe’s films and videos transcend academicism and develop complex signification and emotional affect. Some, such as his “crying film” and his hideously graphic karaoke music video, go much farther, turning emotional life inside-out. The sickening Touch Me Karaoke uses pathetic fallacy as therapy for phallic pathology. His Texas commission, TB TX Dance, is rich with sophisticated reference to high-art modernist masters such as Andy Warhol, Bruce Conner, and Peter Kubelka, and, at the same time, positively invested in, not just pop art, but pop culture—he loves Toni Basil and MTV as much as he does Bruce Conner and Canyon Cinema.

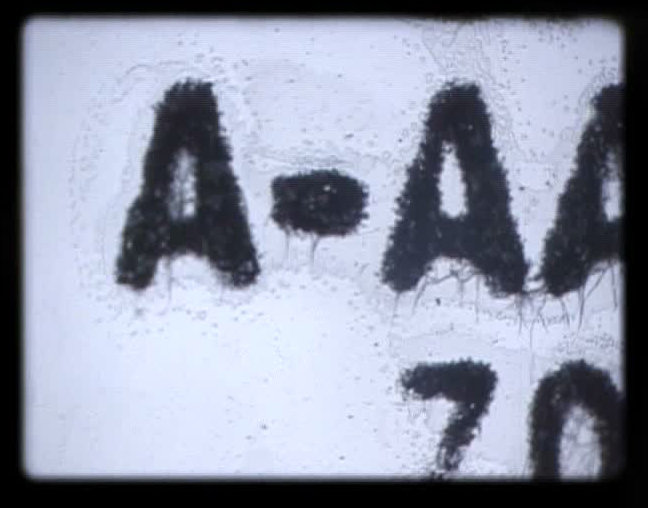

AAAAA Motion Picture’s title recalls Bruce Conner’s classic, A Movie, but Beebe starts his title with a stutter, “A A A A A,” that mimics his film’s flickering, frame-by-frame syntax. AAAAA Motion Picture is one of his most intellectual films, but when presented live it rises into song, exhorting the audience to chant the film’s drone “A”, a tone on the musical scale of some multiple of about 27.5 Hz. Thus, as with Touch Me Karaoke, the audience becomes part of the film’s audio. Viewer participation in the audio of AAAAA explicitly addresses the film’s diagnostic message about the me-first impulse of capitalists clamoring to be first in the phone book by naming their enterprises “Acme,” then “AAcme,” “AAAcme,” “AAAAcme,” and “AAAAAcme”. . . eventually the “AAAAAA” overwhelms the “Acme.” The hopelessly hopeful scramble to the front of the line is saved from infinite regress and transformed into Buddhistic bliss when the audience starts humming the “AAAAA” tone that Beebe has abstracted from the melee at the front of the competitive queue. Through this unusual approach to abstraction, the film’s audience is recruited as a unified tonic community—if left-oriented filmmakers are doomed to preach to the choir, Beebe at least tunes up the choir.

Beebe’s film S A V E ends with the photograph of the “SAVE” sign from Robert Frank’s seminal photography book, The Americans (Paris, 1958). Frank’s original SAVE sign is a beat-generation image of America. Beebe’s film, somewhat like Hollis Frampton’s (nostalgia), saves Frank’s SAVE, and like Frampton, looks backward in order to move forward—a diagnostically recursive gambit.

Strip Mall Trilogy moves from apparent visual and semiotic chaos in Part 1 toward a new application of Hollis Frampton’s and Su Friedrich’s abecedarian methodologies. In Strip Mall’s Part 2, language is strained through a Peggy Ahwesh-like soundtrack in which a lo-fi indie/punk band backs a five-year-old girl wailing her ABCs. Her song’s full-throttle climax resembles the coda of Lynne Sachs’s Wind In Our Hair, where the experimental music of Juana Molina accompanies the explosive end-credits of an otherwise meditational narrative about adolescent girls practicing self-empowerment. As in other Beebe films—e.g. A Woman, A Mirror² and Touch Me Karaoke—Part 2 of Strip Mall Trilogy affirms feminism, genuinely collaborating on the DIY music with film-scholar Nora Alter’s irrepressible five-year-old daughter, Arielle. And after this climax, in Part 3 comes the retro-modernist beauty of strip-mall versions of 1950s abstract-expressionist-influenced street photography.

More recently, Beebe’s video installation, Congratulations (One Step at a Time) extends his feminism to a critique of educated women’s submission to mall culture. In this single-shot film, a row of college-graduated women in academic gowns stretches horizontally across the background space, and in the foreground a stairway stretches diagonally between lower left and upper right; the question is, does the stairway lead up or down. The answer is sixty-two contiguous minutes (looped to infinity in installation) of close-ups of steadily downward footsteps, as men and—most notably—women, clomp down the stairs to take their place in the ranks of the processed. The video’s kicker is that most of the women—in the year 2014 CE—are shod in motley super-high heels. The women are “moving on up” by stepping steadily downward in their higher and higher heels, heels that serve as ambient pedestals and prosthetic equalizers that seemingly make them taller, but only do so through fakery, fetish, fashion, consumerism, conformity, distraction, hobbling, and—down the road—physical disability. This is a straight documentary filmed at a real university.

Despite his sometime intellectualism, many of Beebe’s films are not at all academic. The exhilarating Last Light of a Dying Star is a multi-projector film that re-purposes and celebrates West Coast minimalism (Terry Riley’s In C), while mourning the waning of celluloid by indirectly referencing the cosmic scope and beauty of films such as Brakhage’s Dog Star Man and of Stan Vanderbeek’s East-Coast-maximalist expanded cinema. Since Last Light of a Dying Star is a work that requires Beebe’s presence to orchestrate the many projectors, the audience on his tour stop at Austin’s Experimental Response Cinema in 2015 is particularly fortunate—they are among the few who will have a chance to see this “film,” a major work of great charm and serious ambition.

And, though the title of Historia Calamitatum sounds intellectual, Beebe’s crying film, like Scott MacDonald’s 1983 essay, “Confessions of a Feminist Porn-Watcher,” (Beebe’s film is not about pornography), personally probes masculinity and is unguarded enough to add consequential substance to the idea of experimentation in cinema. Opening itself wide to a loved, but damaging culture, the film is full of wounds and wounding, and it catalyzes critical conversation.

These are some of my picks of the larger corpus of Beebe’s work; his are communitarian works that reward individual analysis, and are most exhilarating when presented by Beebe in first-person performance followed by discussion (See endnote 1).♦

–

¹Probably the best guides to Roger Beebe’s films are his own comments—for instance, the captions accompanying his postings on Vimeo. Also, though the Vimeo-posted films are useful for review, Beebe’s work is medium- and performance-specific. Though it is beyond the scope of these notes, Beebe’s work should be considered in the context of works such as Ken Jacobs’s Nervous System performances, Valie Export’s Abstract Film No. 2 (2014), and recent presentations by Aura Satz, Sandra Gibson and Luis Recoder, and Daniel Barrow, as discussed in Erika Balsom’s essay, “Live and Direct: Erika Balsom on Cinema as a Performing Art,” Artforum (September 2014, pp. 328-333 and 398), and also in the context of the films discussed in the issue of Millennium Film Journal (Nos. 43/44, Summer/Fall 2005) that is devoted to paracinema and performance.

²Beebe’s film collaborates with and studies a woman choreographer, Sara L. Smith, relating her dance to Amelia Earhart’s flying and to a photo by Francesca Woodman.

–

Ron Green is Professor Emeritus of Film Studies in the Film Studies Program and the Department of History of Art at Ohio State University. His books include Straight Lick: The Cinema of Oscar Micheaux, reviewed in the TLS, London Review of Books, Washington Post, NPR, and Film Q., and With a Crooked Stick─The Films of Oscar Micheaux. His essays on the film/video loop have appeared in Millennium Film Journal in Spring 2012, Senses of Cinema in December 2012, and in Boucle et repetition, Univ. of Liege Press, 2015. He has published or is working on articles on Christoph Girardet, Michael Snow, Teresa Hubbard/Alex Birchler, Jacob Holdt, Jennifer Reeder, and Ann Hamilton.